Rate Cuts Are Here

The Fed cut rates by 0.25% in September, citing a softer labor market. While tariff-related inflation may still emerge, more cuts could follow depending on jobs and prices. Lower rates may weigh on savers but could support stocks if the economy avoids recession.

Key takeaways

The Fed cut its benchmark rate by a quarter of a percentage point, responding to a softening labor market.

Tariff-related inflation may still be coming, as companies start passing costs to consumers.

More rate cuts are likely to follow, but the exact timing and magnitude will depend on how jobs and inflation evolve.

Rate cuts may reduce what savers can earn on short-term fixed income, but could be constructive for the stock market if the economy continues to avoid recession.

As investors had widely expected, the Fed cut interest rates at the September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting—responding to job-market data that has appeared to weaken materially in recent weeks.

The 25-basis-point reduction may have disappointed some investors who were hoping for a jumbo cut (a basis point is 0.01 of a percentage point). But it likely reflected a compromise move between members of the FOMC who are more worried about inflation, and those who are more worried about unemployment. The move brought the central bank’s benchmark federal funds rate to a range of 4.0%–4.25%.

Read on for more about the Fed’s thinking, plus what the latest developments may mean for stocks, mortgage rates, and more.

A compromise decision from a conflicted Fed

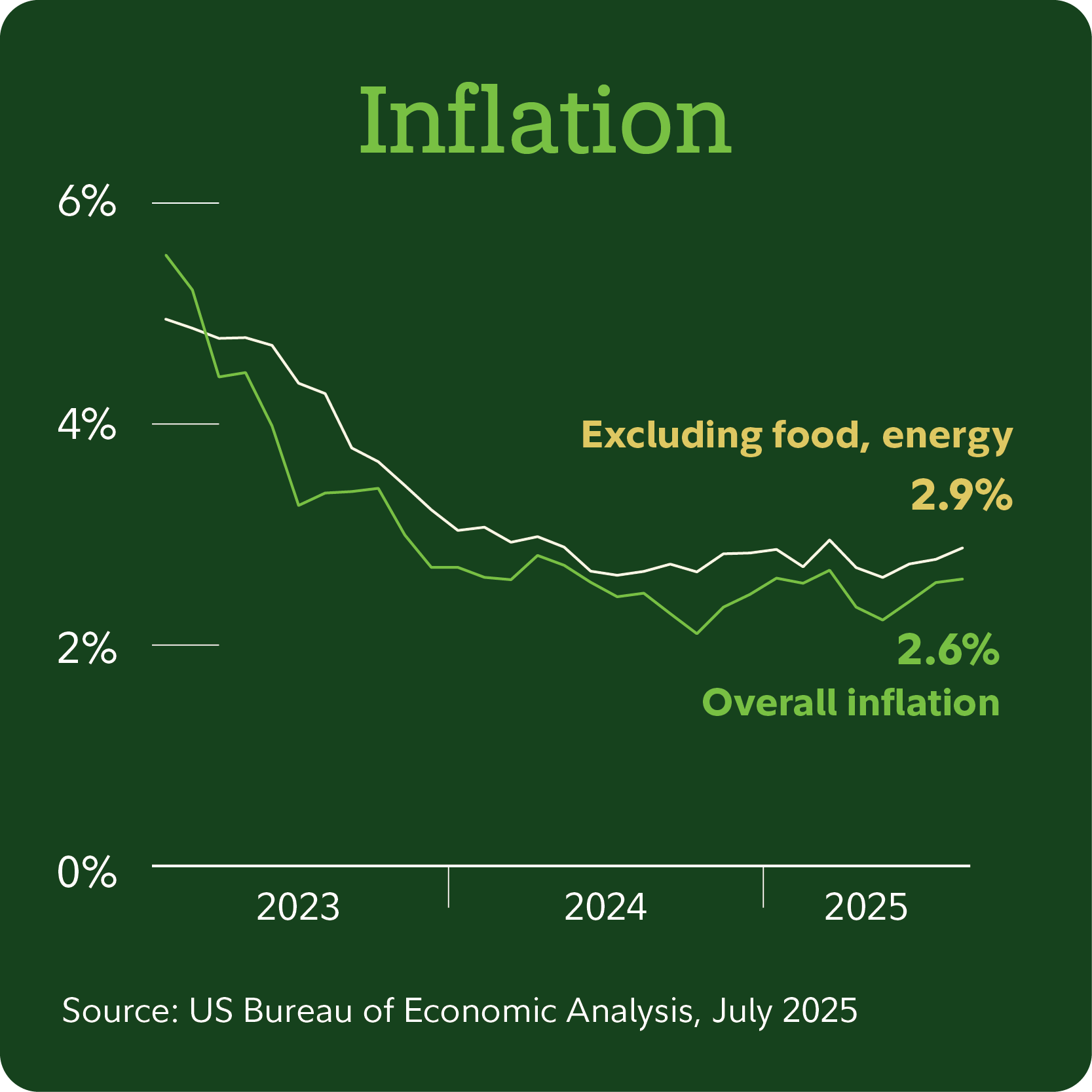

The Fed has a dual mandate of keeping unemployment low while also keeping inflation low and stable. Right now, those 2 aims are in tension. A weakening labor market weighs in favor of bringing rates down, because lower rates can help foster economic growth and job creation. However, inflation is still too high compared with the Fed’s 2% inflation target and has been ticking up in recent months. That weighs in favor of leaving rates high, because higher rates help slow inflation (by slowing the overall economy).

The cut decision shows that most FOMC members see the weakening jobs market as the more pressing concern, but differences remain. Some members have been more vocal about the need to step in to support the job market, while others have expressed greater concern about inflation. One member dissented from the central bank’s decision at the September meeting—instead voting to cut rates by a half a percentage point.

So while there was some chatter from investors that a 50-basis-point cut could be on the table, such a large move likely couldn’t garner enough support from the Fed’s divided members. “Cutting by 50 basis points is harder to do than just 25 when there isn’t full consensus,” says Kana Norimoto, the macro strategist on Fidelity’s fixed income research team who covers the Fed.

What is going on with the job market?

Weakening jobs numbers in the past few weeks effectively sealed the deal on the cut decision.

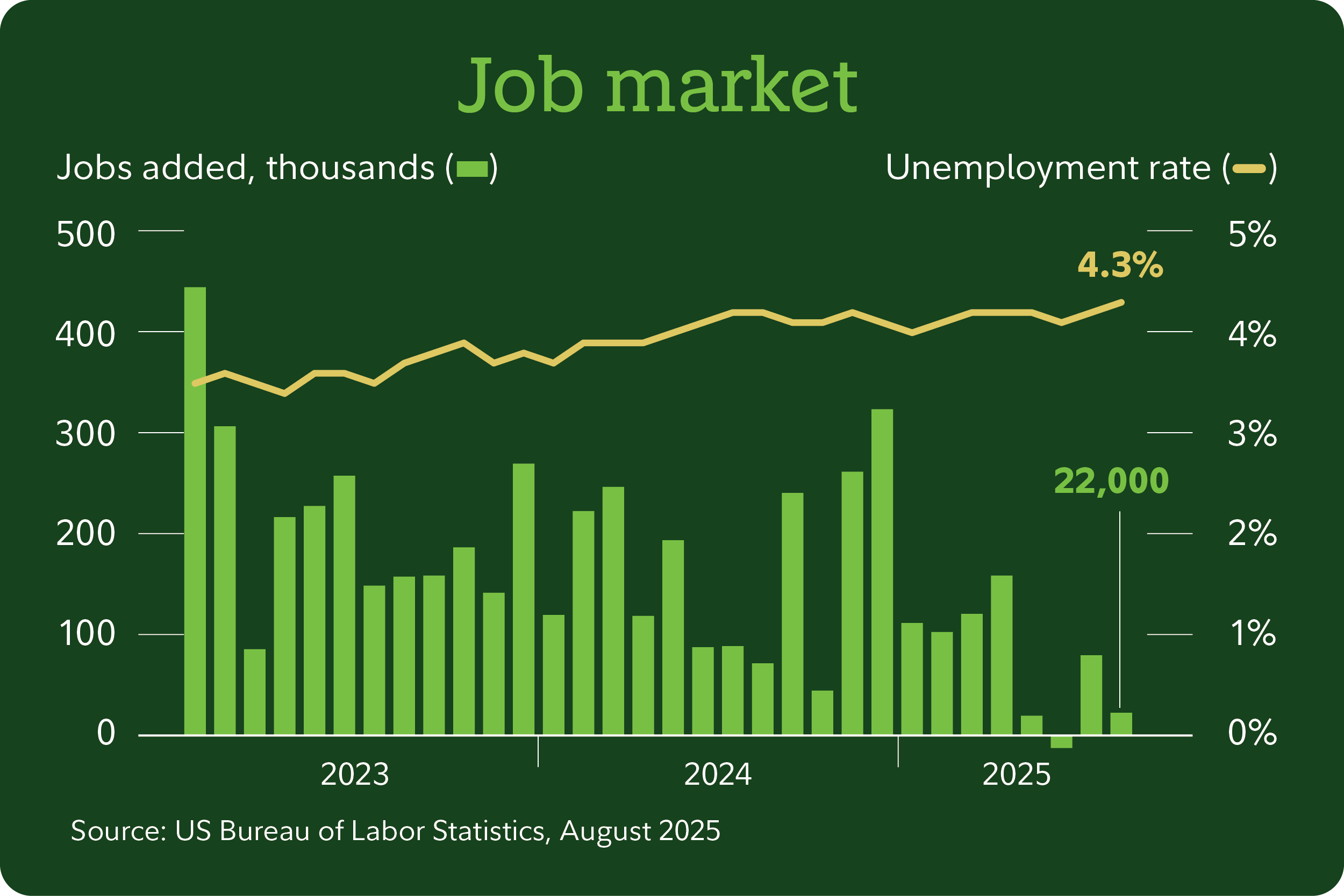

Recent stark revisions to payroll numbers showed that the US has been creating far fewer jobs than previously reported. Norimoto says those numbers reflect slowing demand for labor, which has been met with a decline in the supply of labor—driven by a steep decline in immigration. She adds that the revisions weren’t a complete surprise, because the flow of immigration had dropped significantly and other measures of job growth had already shown signs of flagging. Unemployment also rose in the most recent reading, ticking up to 4.3% in August—its highest level in almost 4 years.

Jobs added represented by growth in nonfarm payrolls.

That said, there aren’t yet any signs of rapid or severe deterioration. “We aren’t seeing a lot of layoffs or firings,” notes Andrew Garvey, the lead monetary policy analyst on Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team. “The labor market definitely looks weaker than it did a few months ago, but it doesn’t look dire.”

Tariff-related inflation could be still to come

Although inflation has crept up slightly in recent readings, the modest pace of price increases has surprised many economists—who expected tariff-related inflation to begin showing up more significantly over the summer. “As of right now, we haven’t seen a huge reacceleration of inflation,” says Garvey.

Inflation represented by the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index.

However, Norimoto says those inflationary impacts might still be to come, just at a greater lag than initially expected. Tariffs are paid by importers, who generally must choose between taking a hit to their profits or raising the prices they charge consumers. As tariff policies remained in flux for much of the year, many companies held off on price hikes—waiting for greater clarity on trade deals and reluctant to be the first among peers to raise prices and risk seeing shoppers switch to cheaper brands.

Some companies stockpiled inventory early in the year, before tariffs were imposed, and have been working down those reserves. Others were, until recently, able to sidestep tariffs by routing goods through third countries with lower tariff rates.

“Companies have been in this holding pattern,” Norimoto says. But with greater clarity on trade deals since August, there are indicators that some companies may start trickling out gradual price increases—potentially avoiding a sudden shock to consumers but putting slow continued upward pressure on inflation over the coming months. “We may start seeing prices increase this coming quarter into next year,” she says.

How many more rate cuts could be coming?

The Fed also released a freshly revised dot plot, a key chart that shows where FOMC members believe interest rates may be headed.

The dot plot showed that a median of Fed members expect the fed funds rate to fall to a range of 3.5%–3.75% by the end of 2025. That would imply 2 more cuts of a quarter of a percentage point at its remaining 2 meetings this year. A median of members expect the rate to fall to a range of 3.25%–3.5% by the end of 2026, implying 1 more cut next year.

Source: Federal Reserve Board Summary of Economic Projections, September 2025

That said, these dots represent personal estimates of individual members rather than a commitment from the Fed itself. And the Fed’s narrow balancing act between jobs and inflation means the scales for future rate decisions could easily still tip.

Thus far the job market has appeared merely stagnant—with low hirings and low firings—but the Fed will be watching for whether indicators worsen, which could lead it to cut more aggressively. For example, the unemployment rate among 16- to 24-year-olds, considered an early indicator of turning points, recently rose above 10%. However, if the job market improves but inflation pushes higher, the Fed could cut more gradually.

What rate cuts may mean for consumers and investors

It’s important to understand that the Fed only controls very short-term interest rates. The Fed does not set interest rates on mortgages, CDs, or bonds, though its actions influence these rates.

The impact for consumers may be most immediately felt with lower interest payments on debt with rates tied to the prime rate. Savers and investors may notice the impact most directly on very short-term fixed income, like money-market funds and short-term Treasurys and CDs, which are likely to experience falling rates.

Interest rates on longer-term debt like 30-year mortgages and 10-year Treasurys did not fall as the Fed was cutting rates late last year. Jake Weinstein, senior vice president on Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team, says there are no guarantees as to how long-term rates may react this time. “The range of possible outcomes is wider,” he says. “Long-term rates are more likely to follow the path of economic growth and inflation. If jobs numbers disappoint and inflation is weak, long-term rates may fall. If the labor market improves and inflation accelerates, then long-term rates may rise.”

For stock investors, falling rates have historically been a mixed bag—sometimes corresponding with a declining market and sometimes with a rising market. However, Denise Chisholm, Fidelity’s director of quantitative market strategy, says that this time around there may be a few reasons for optimism.